6. Cardiac Disorders

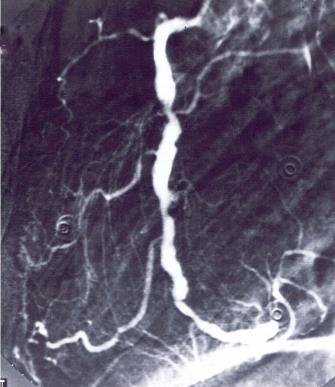

CAG showing right coronary artery with multiple stenoses. Patients with iscaemic disorders are evaluated according to their symptoms and their functional class and must be advised on this basis in connection with air travel.

Photo: Cardiology Laboratory, Rigshospitalet.

General

When transporting cardiac patients by air, the following points should be taken into account:

• Low oxygen pressure in the cabin means decreasing oxygen supply to the heart and all other

organs.

• Immobility on long distance flights. This can cause venous stasis and in some cases the risk of

deep venous thrombosis (DVT).

• Increased abdominal distension, which can impair respiration and cause pressure in the chest

cavity.

Can be mistaken for angina pectoris.

Most cardiac patients undertake air journeys without any trouble at all. However, if the patient is unstable with a low angina pectoris threshold, is significantly cardiac insufficient, or has a cyanotic cardiac disorder, a number of problems will present themselves.

During long flights, patients are advised to wear knee-length graduated compression stockings, and they should be urged to perform vein pumping exercises and, if possible, to move around the aircraft several times during the flight. In heart patients having multiple risk factors of developing a DVT and not receiving anticoagulant therapy, low-molecular-weight heparin should be con-sidered. Concerning thromboembolic prophylaxis please see Chapter 1.

Ample intake of liquid should be advised, but not too much coffee, tea or alcohol, which all cause dehydration. Liquid intake should be in the form of non-carbonated drinks in order to avoid abdominal distension. Medicine should be on hand in the hand luggage locker and should be in its original packaging so that, in case of a sudden deterioration in the patient’s condition, others can see what it is.

Cardiac ischemia

Chronic stable angina pectoris

If the patient has angina pectoris with a well-defined angina threshold and a good response to nitro-glycerine, air travel presents no significant risk. The patient should have help with baggage, and, in order to minimise stress during flight transfers, airport conveyance (wheelchair, etc.) should be arranged in advance.

Patients with stable angina pectoris but with a low angina threshold may require oxygen during the flight. Oxygen treatment should be arranged with the airline in advance. If the patient is familiar with using oxygen, he can travel unescorted. If not, he should be escorted by a physician or a nurse.

Recent/unstable angina pectoris

A condition involving a recent or altered angina pectoris pattern – usually accompanied by pain brought on by only mild exertion or when at rest – will most usually be an element of the acute ischemic syndrome and a forewarning of acute myocardial infarction (AMI). The patient will not be allowed on commercial flights, and even transportation by a well-equipped air ambulance should only be undertaken if in situ treatment is unavailable.

The treatment of unstable angina pectoris consists of bed rest, oxygen therapy, administration of morphine substitutes, intensification of anti-angina drug treatment, and cardiac care supervision. If the angina pectoris disappears, the patient should be fully mobile before making a decision about possible air travel. An exercise ECG should be carried out to ensure the patient is stable. After that, the same guidelines that apply to stable angina pectoris should be followed. If the condition does not stabilise within a few days, a coronary arteriography (CAG) should be done and, if necessary, followed by a PCI (Percutaneous Coronary Intervention) or a bypass surgery.

Immediate air transport of unstable heart patients

In the few cases where adequate treatment cannot be obtained locally and air transportation is preferred, it will be carried out as follows:

Reclining transportation in an air ambulance escorted by an anaesthetist and an anaesthetic or intensive care nurse and if possible with access to cardiological advice. Cardiac monitoring, sufficient oxygen for the whole transportation, transcutaneous pacing equipment, resuscitation equipment, and medicine for acute thrombolysis treatment should all be available. Ideally, transportation should be carried out by aircraft in which cabin pressure can be maintained as close to 1 atm as possible.

Acute myocardial infarction, AMI

The modern treatment of AMI with acute PCI or thrombolysis normally minimises damage of the myocardia, giving rise to fewer complications and a shorter admission time.

• Uncomplicated AMI

Usually, airlines accept patients with uncomplicated AMI (patient free of pain within a few days,

no significant arrhythmia, well-compensated, and fully mobile after one week), travelling

unescorted on a commercial flight after 7-10 days.

• Complicated AMI

Patients with complicated AMI should be evaluated individually.

Relevant investigations should be performed such as CAG, echocardiography, and event

recording, and the patient should be treated according to the findings. In general, the

complications must be treated and the patient mobilised and stable without any significant

cardiac symptoms before he or she can be transported unescorted by commercial flight.

If the patient, despite having received relevant treatment, still has persistent symptoms like heart failure, or angina pain, the transport needs to be planned according to the guidelines for the current condition (please see the relevant passage).

If a patient with recently occurred AMI is residing in a place without treatment facilities, trans-portation by air may become necessary if there are complications that require treatment. Such transportation will then only be carried out under the same conditions as applies to the acute air transport of unstable heart patients, as mentioned in the passage: “Immediate air transport of unstable heart patients”.

In the case of clinically minor infractions, it will often be safest and best to allow the patient to rest for 14 days at the location where trauma occurred, even if there are no treatment facilities.

Heart failure

Heart failure is classified in accordance with the New York Heart Association’s functional classes – NYHA functional class I – IV.

This classification refers only to symptomatology and not at all to the aetiology, which will most often be ischemic in nature but could involve valvular heart disease or primary myocardial disease.

Functional Class I

Includes patients with organic heart disease and whose physical capacity is not limited in any way.

Functional Class II

Includes patients with organic heart disease whose physical capacity is limited to a minor extent.

They are symptom free when at rest or during light physical exertion, but experience dyspnoea, angina pectoris, fatigue, or palpitations at higher levels of physical activity.

Functional Class III

Includes patients who are seriously limited in their physical capacity. They are symptom free when at rest, but experience the above-mentioned symptoms during light physical activity.

Functional Class IV

Includes patients who have symptoms while at rest and who experience an aggravation of these during any and all activity.

Most airline companies have the following rules for transporting patients with heart failure:

NYHA classes I and II

Patients should receive sufficient treatment and may then travel by air unescorted by commercial flight.

NYHA class III

Patients should receive sufficient treatment and, on longer flights, should possibly undergo anticoagulant therapy. The patient may travel by commercial flight but should have help with luggage and a wheelchair at the airport. Oxygen during flight must be considered. If selected, the patient should be accompanied by nurse if the patient is not used to administering oxygen himself.

NYHA class IV

Patients should receive sufficient treatment and should undergo regular anticoagulant therapy. Any arrhythmias must be treated.

Transportation by commercial flight is possible with a medical escort and with an oxygen supply. The most seriously ill patients in this class should be transported by air ambulance.

Arrhythmia

Asymptomatic bradycardia

Patients with asymptomatic bradycardia/block, where not associated with syncope and where monitoring has not revealed any great degree of heart block, may travel unescorted on commercial flights.

Symptomatic bradycardia

Patients with symptomatic bradycardia with or without syncope should not travel before the implantation of a pacemaker. There is no special risk involved for pacemaker patients travelling by air. There is no risk of electrical interference between the pacemaker and the aircraft’s radio/electronics systems. Pacemaker patients may pass through airport security systems, but they must show their pacemaker identification cards.

After the implantation of a fully functional pacemaker, the patient can usually be accepted on a commercial flight after 3 days.

After the implantation of a temporary pacemaker, the patient may be transported by commercial flight when efficient pacing has been ensured. The patient must be escorted, normally by a cardiologist. If adequate pacing cannot be assured, the patient must be transported by air ambulance (see “Immediate air transport of unstable heart patients”).

Paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia

Patients who suffer frequent hemodynamic symptom-producing attacks of paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia should not attempt to travel until they have received sufficient prophylactic treatment or been examined and treated using electrophysiological therapy.

Patients with short non-symptom producing attacks of supraventricular paroxysmal tachycardia may travel by air unescorted.

Chronic atrial flutter

Atrial flutter with a rapid ventricular rate should be regulated before repatriation.

Patients with well-controlled atrial flutter may travel unescorted by commercial flight but should receive oral anticoagulation therapy.

Ventricular arrhythmias

Unifocal ventricular extrasystoles are often harmless, and the patient may travel unescorted by commercial flight.

Multifocal ventricular extrasystoles and attacks of ventricular tachycardia are often life threatening and predominantly manifest themselves as symptoms of an unstable ischemic cardiac disorder. Repatriation may only be undertaken after the patient’s condition has stabilised medically and after the disappearance of ventricular tachycardia. In some cases the implantation of a special defibrillation pacemaker (ICD) may be indicated. Following the implantation of a fully functional ICD, the patient can usually be accepted on a commercial flight after 3 days.

If the patient’s condition does not stabilise, repatriation should be carried out as described under “Immediate air transport of unstable heart patients“.

Heart Surgery

Bypass surgery

After an uncomplicated bypass operation with a satisfactory outcome, the patient will normally be able to travel by air within two weeks.

Patients who have undergone bypass surgery may not lift or carry anything for the first 6 weeks, as this can rupture the sternum scar. For these reasons, luggage assistance at the airport should be arranged for the patient if travelling unescorted.

Special attention should be paid to the legs of those bypass patients who have undergone vein grafting; the patient should wear thigh-length graduated compression stockings as thrombosis prophylaxis.

Patients who have undergone thoracotomy should have a chest X-ray before travelling by air in order to ensure there is no residual pneumothorax.

Patients who have undergone bypass surgery along with supplementary aneurysmectomy or the closure of a ventricular septal defect will have a longer post-operative period of convalescence. Air travel after such an operation must not be undertaken until the patient is mobile and fully stable without symptoms.

Open-heart surgery

After open-heart surgery, such as heart valve operations, the patient will usually be accepted unescorted on a commercial flight after 3 weeks, if the postoperative course has been without complications. If the patient is travelling unescorted, luggage assistance should be arranged.

Heart transplantation

Should be assessed individually.

PCI

After an uncomplicated, elective PCI with or without stent placement, the patient will usually be accepted on a commercial flight after 3 days.

Cardiac ablation

After a successful ablation, the patient will usually be accepted on a commercial flight after 3 days. One should take into account that patients flying within the first week after an ablation have a high risk of developing a DVT (concerning thromboembolic prophylaxis please see Chapter 1).

001. Frontpage

001. Foreword

001. Contributors

001. Aeromedical Problems

012. Planning the Air Transportation of Patients

013. Airline Requirements

015. Transportation of Disabled Persons

016. Cardiac Disorders

019. Gastrointestinal Disorders

010. Central Nervous System Disorders

011. Ear, Nose, and Throat Disorders

012. Eye Disorders

013. Mental Disorders

014. Gynaecological and Pregnancy Problems

015. Transportation of Sick Children

016. Infectious Diseases

017. Orthopaedic Injuries

018. Cancer

120. Acute Mountain and Decompression Sickness

021. Burns and Plastic Surgical Problems

122. Airsickness

123. Jet Lag

124. The STEP System

125. Specialised Transportation of Patients

126. First Aid on Board – Legal Considerations

27. The History of Air Transportation of Patients

28. Oxygen supplementation in flight - a summary

Latest update: 19 - 09 - 2022