9. Gastrointestinal Disorders

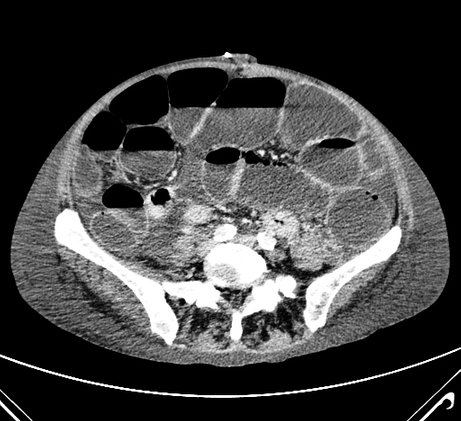

CT scan of a patient with ileus. Patients with ileus or subileus may not travel by commercial airliner, as the reduced cabin pressure will further increase bowel distension and risk of perforation.

Photo: Dept. of Radiology,

Herlev Hospital.

General

When flying in a commercial aircraft at cruising altitude, the cabin pressure is ¾ atm. As a consequence of the reduced cabin pressure, gas in the peritoneal cavity and within the gastrointestinal tract will expand approximately 38%. Trapped air can cause problems, for instance, where the patient has ileus, or if the gastrointestinal wall is weakened by recent suturing, clip, infection, or ulcer, as a perforation may occur.

Overall, bowel function should be restored and normal before the flight. There must be no signs or symptoms of obstruction within the gastrointestinal tract (nausea, vomiting, meteorism, no passage of stool or flatus within the last days), or diarrhoea that may be caused by gastroenteritis.

In general, a patient can be transported by aircraft 5 days after laparoscopic surgery for conditions such as appendicitis, cholecystitis, or gynaecological conditions, and 10 days after laparotomy, since paralysis is prolonged and suture lines and anastomoses must be stable and capable of withstanding slight abdominal distension during the flight. After diagnostic laparoscopy without complications, air transportation is allowed after 2 days, since the insufflated gas (most commonly CO2 is used) will have been completely resorbed by this time.

Gastrointestinal diseases

Gastrointestinal bleeding

Patients are accepted after acute anaemia, when the haemoglobin concentration is ≥5,3 mmol/l (8,5 g/dl).

After upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage, patients are normally accepted after 7-10 days, without signs of bleeding. The airline’s medical departments may, depending on the individual company guidelines, allow earlier transportation if it has been reliably proven that the bleeding has stopped (either spontaneously or after endoscopic haemostasis). The best documentation for this is endoscopic, or alternatively repeated haemoglobin measurements showing stable or increasing haemoglobin concentration concurrently with stools having normal colour again. After gastric or duodenal haemorrhage due to an ulcer or gastritis, PPI treatment should be initiated. Patients with bleeding oesophageal varices should be treated with endoscopic ligature (‘banding’) and must have a stable or increasing haemoglobin concentration before air travel. If the history indicates an increased risk of re-bleeding in an otherwise correctly treated patient with bleeding oesophageal varices, the patient should have a medical escort or an air ambulance / PTC should be considered.

Appendicitis

Patients with acute appendicitis may not be transported by aircraft. The main reason is the risk of perforation and septic shock. The patient should be operated locally. If this is not possible, the patient should be immediately treated with antibiotics and transferred with a medical escort as soon as possible by air ambulance to the closest medical facility.

After an uncomplicated appendectomy with an uncomplicated postoperative course, patients will usually be accepted after 5 days and can travel, seated (on intercontinental flights in business class seat) and unescorted, provided that normal bowel function has been restored, which is usually after 2-3 days. The airline may accept patients earlier than the 5th postoperative day based on individual assessment.

Intestinal obstruction

In patients with partial or complete intestinal obstruction, regardless of whether the cause is paralysis or mechanical, distension of the intestines will quickly develop. Flying will always aggravate this condition due to further distension, which may increase the risk of perforation and ischemia leading to gangrene. The pain caused by distension may result in vasovagal reactions. Therefore, patients should be treated locally before being transported whenever possible. For evacuation by air due to lack of treatment facilities, an air ambulance with cabin pressure equivalent to sea-level pressure must be used. Before and during the flight, the patient should have a nasogastric tube with suction, and should be escorted by a physician.

Diverticulitis

Air travel is contraindicated if the patient has symptoms of diverticulitis (especially if the patient has a fever), due to the risk of perforation and sepsis. The patient can be transported after surgery or antibiotic therapy when there are no more symptoms and their condition is stable.

Colostomy and iIeostomy

Patients with a newly constructed colostomy or ileostomy must wait a few days after normal bowel function has been re-established before travelling by commercial aircraft. At least 10 days should pass after surgery if the stoma has been placed in relation to a laparotomy, which is still most often the case. If after 10 days the patient or relative is still not familiar and comfortable with changing and handling the colostomy bag in public areas and aircraft, then a nurse or physician must escort the patient. Patients with a stoma should also be aware that the reduced pressure in the aircraft will lead to increased output. Therefore, the colostomy bag should be emptied just before the flight, and extra bags should be readily available.

Biliary diseases

Cholecystolithiasis and bile duct stones

Following a single gallstone attack, the patient may usually travel by air unaccompanied after 1 day without pain, and should have analgesics as tablets and suppositories available for the trip. There should be no signs of occlusion of the biliary tract (these signs include elevated liver enzymes with or without jaundice). If there have been several attacks over a short period of time and surgery has not been done, 3-5 days without pain should pass before transportation. Patients with bile duct stones should undergo ERC with stone removal or stenting, otherwise there is a risk of acute complications during the flight (attacks of severe pain, acute pancreatitis, cholangitis with sepsis, or even septic shock).

Acute cholecystitis

Acute cholecystitis is a contraindication to air transport for the same reasons as appendicitis (risk of rapid deterioration and perforation with sepsis), and the patient should, if possible, be operated on before repatriation. If surgery is not an option, the clinical condition must have been stabilised through antibiotic treatment and the patient mobilised before repatriation is planned. This usually requires 6-10 days in hospital. After laparoscopic cholecystectomy with an uncomplicated recovery, the patient can be air lifted from the 5th post-operative day. After open cholecystectomy for cholecystitis, 10 days must pass. In both cases, bowel function must have been restored. The airlines may authorise earlier transport based on an individual assessment.

Pancreatitis

In case of gallstone pancreatitis, the bile duct stone(s) must have been cleared spontaneously (this can be demonstrated with MRCP and normalised liver function tests) or removed (by ERCP), or the common bile duct must be drained with a stent, since recurrence with severe pain can occur quite suddenly. In addition, the below criteria should apply to patients with gallstone pancreatitis and pancreatitis of other aetiology.

Criteria for air travel after pancreatitis: The patient can be transported by air when amylase (or lipase, which is used in some countries) is normal, the patient is without pain, can eat, has normal bowel function, and has been mobilised. In uncomplicated acute pancreatitis, this is usually achieved after 5-7 days, but it may take a longer time.

In approximately 5% of cases, the condition develops to severe pancreatitis (haemorrhagic or necrotising pancreatitis). The patient will often require intensive care or must be evacuated to a facility with adequate treatment facilities. Depending on the complications and course, subsequent repatriation may often require air ambulance / PTC.

Abdominal trauma

Abdominal trauma may result in organ injury and a resulting acute or delayed (up to several days) haemorrhage. A traumatic subcapsular hematoma of the spleen may suddenly burst after a week or even later. Blunt abdominal trauma may also result in injury that may go unidentified for several days (for instance, duodenal injury or pancreatic injury). Therefore, it is mandatory that such patients be thoroughly studied, including a complete CT scan of the chest and abdomen prior to the planning of transport. The haemoglobin concentration must be followed for several days and remain stable.

001. Frontpage

001. Foreword

001. Contributors

001. Aeromedical Problems

012. Planning the Air Transportation of Patients

013. Airline Requirements

015. Transportation of Disabled Persons

016. Cardiac Disorders

019. Gastrointestinal Disorders

010. Central Nervous System Disorders

011. Ear, Nose, and Throat Disorders

012. Eye Disorders

013. Mental Disorders

014. Gynaecological and Pregnancy Problems

015. Transportation of Sick Children

016. Infectious Diseases

017. Orthopaedic Injuries

018. Cancer

120. Acute Mountain and Decompression Sickness

021. Burns and Plastic Surgical Problems

122. Airsickness

123. Jet Lag

124. The STEP System

125. Specialised Transportation of Patients

126. First Aid on Board – Legal Considerations

27. The History of Air Transportation of Patients

28. Oxygen supplementation in flight - a summary

Latest update: 29 - 02 - 2020